Orchestrating Success

TL;DR: How Vinted standardizes large-scale decentralized data pipelines.

When we started migrating Vinted’s data infrastructure to the cloud, we set out to create a decentralized way of working. The idea was simple: teams know their data best, so they should be fully empowered to build, own, and operate their pipelines without a central platform team getting in the way.

In that early phase, this worked reasonably well. Teams were moving fast, experimenting, and shipping value. They orchestrated their pipelines independently, inside their own domain. But as the platform grew, reality caught up with us: handling dependencies between decentralized teams requires a sophisticated solution.

In practice, teams were constantly using each other’s data assets. A marketing model would rely on product events; a finance report depended on operational data; a machine learning feature set pulled from three different domains. The business logic was naturally cross‑cutting, but our orchestration model pretended that domains were islands. This led to a subtle but very real problem: coordination moved from code into endless meetings.

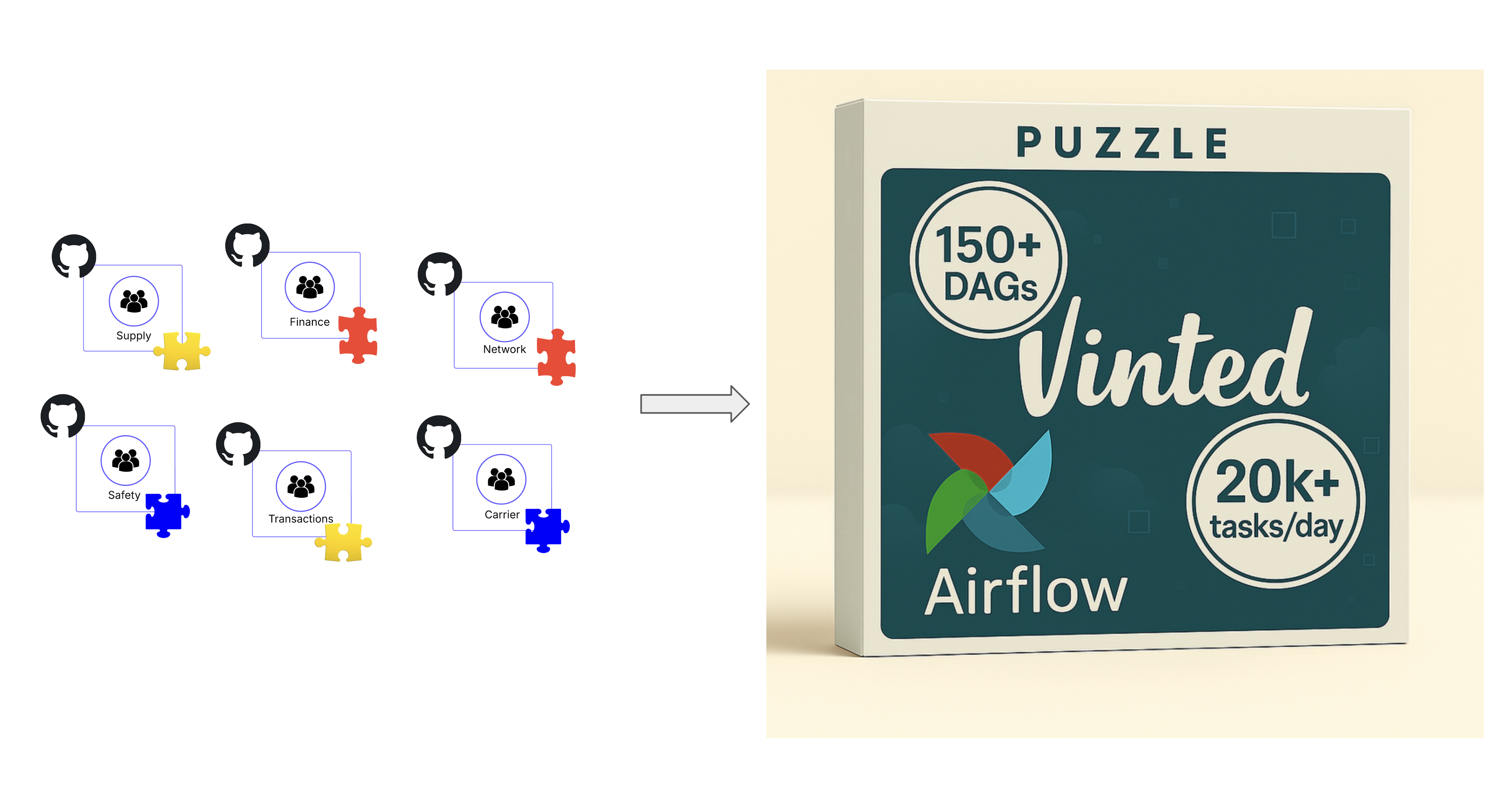

We were left with a pretty hefty task to solve: how do we make sure that these domains naturally fit together, as to complete Vinted’s puzzle of data pipeline orchestration?

The Dark Side of Decentralization

The goal of our decentralized setup was to let teams work autonomously, without constantly leaning on a central data platform. They got their own infrastructure in GCP, their own dbt project, and were expected to run their own pipelines on an Airflow instance provided by the data platform team.

At the same time, we didn’t have Airflow experts scattered across the organization, and we didn’t want to create that requirement. Asking every team to hand‑craft DAGs and become fluent in Airflow would distract them from doing what they do best: creating impactful data models that positively influence Vinted.

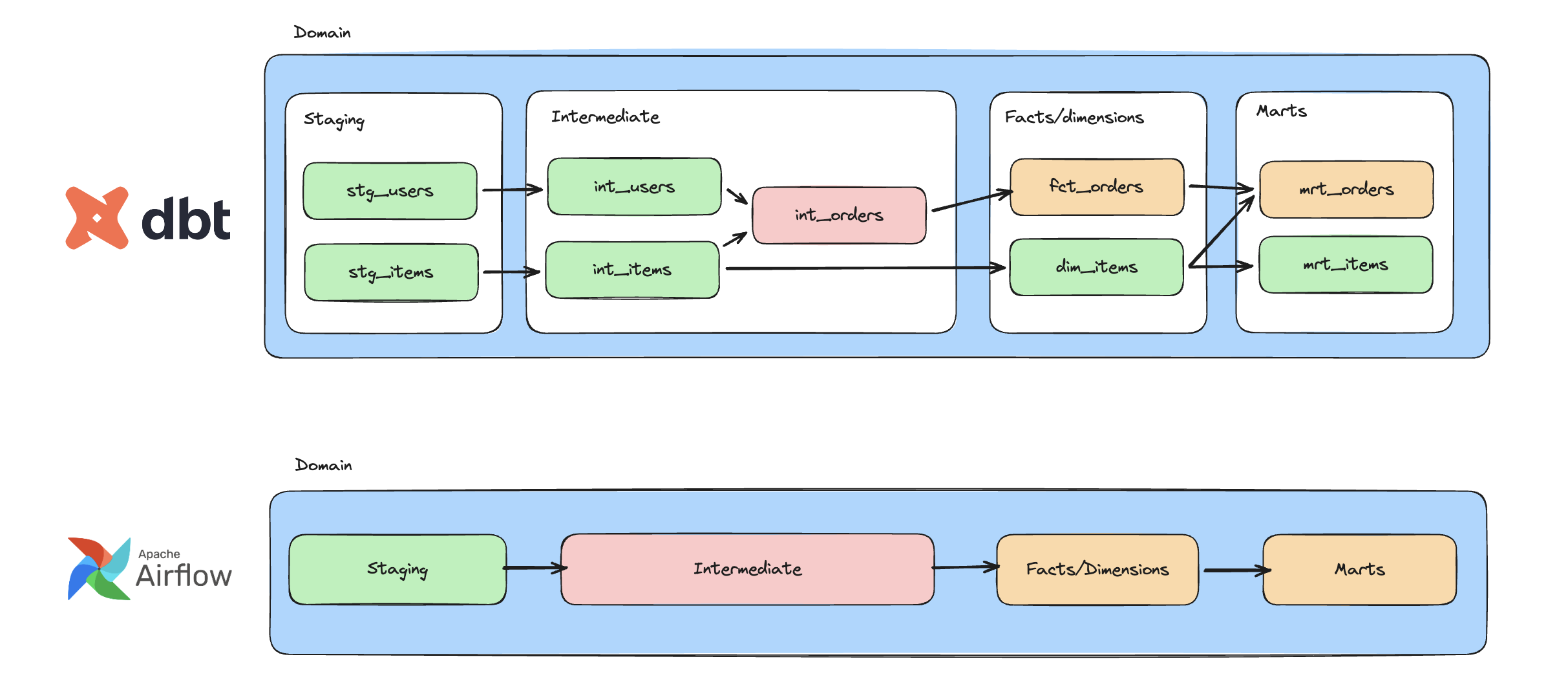

In fact, the “classic” way to run dbt with Airflow leans into that idea: keep Airflow simple and let dbt handle the complexity. You schedule a small number of tasks, often just a dbt run executed as a Bash command, and dbt resolves the full dependency graph internally. Airflow doesn’t try to mirror dbt’s model-level lineage; it just triggers the job and reports whether it succeeded.

We followed the same philosophy, but adapted it to our scale and constraints. A single end-to-end execution was simple, but it didn’t fit our cost profile: if something failed late in the run, the easiest recovery was often to rerun the whole job, which meant recomputing (and paying for) a lot of already-finished work, including some very large tables. To keep retries cheaper and failures more contained, we split execution into layers: one Airflow task per dbt “layer”. Airflow would call dbt with “run the staging layer,” “run the fact layer,” “run the mart layer,” and dbt would take care of the rest. Inside the job, dbt figured out the dependency graph within that layer and executed the models in the right order

This kept things approachable, but it had sharp edges. If an unrelated staging model broke, the entire staging layer task would fail and everything downstream would be blocked. The figure shows an example:

The dbt lineage shows that mrt_items should complete without problems in the case that int_orders fails. However, due to the fact that Airflow doesn’t have this granularity, it never even starts the jobs downstream from the intermediate layer. Data that didn’t actually depend on the broken model still arrived late. This was only the beginning of our troubles.

This “dbt handles the graph, Airflow runs the job” approach works extremely well at small scale. However, once you’re dealing with thousands of models spread across ~20 teams, the lack of model-level transparency becomes a real operational problem, especially when dependencies cross team boundaries. When something breaks, it’s no longer obvious what’s actually blocking what, which missing dependency caused the failure, or who owns the upstream piece that needs fixing. In a decentralized setup, that ambiguity is expensive: tracing issues turns into detective work, and responsibility becomes harder to pinpoint. The same lack of visibility forces teams to wait for an entire upstream pipeline to finish, because they can’t reliably tell when the specific piece they depend on is actually done. You’d hear questions like:

- “At what time can I assume your daily job is finished?”

- “If your pipeline fails, how will I know?”

- “Can we align our schedules so my pipeline doesn’t start too late?”

We had successfully decentralized ownership, but we had accidentally introduced fragility in the hand‑offs between teams.

The Rise of our DAG Generator

We believe decentralized teams are what we need to scale, as Vinted grows. So we needed a way to remove the cognitive load of “orchestration trivia” from domain teams, especially around cross‑domain dependencies.

The key design goal was this: Let teams think in terms of data models and lineage, not in terms of pipeline scheduling and cross‑pipeline wiring.

To get there, we focused on two things:

- Abstracting away pipeline creation, so engineers didn’t need to hand‑craft DAGs and dependency chains

- Standardizing the way dependencies interact, so relationships between data assets were expressed and enforced consistently

We already had the perfect source of truth for dependencies: the dbt manifest. It knows which model depends on which, how data flows through the domain, and where the boundaries between sources and transforms lie.

So we built a DAG generator that:

- Reads the dbt manifest

- Understands the full lineage within a domain

- Unfolds that lineage into a task‑per‑model setup in Airflow

By unfolding the lineage into a task‑per‑model structure, we gained granularity and flexibility. Suddenly, we weren’t just running “the staging layer”, we were running concrete, addressable units of work that mapped directly to dbt models. That opened the door to do something much more powerful across domains.

Decentralized Domains, Centralized Dependencies

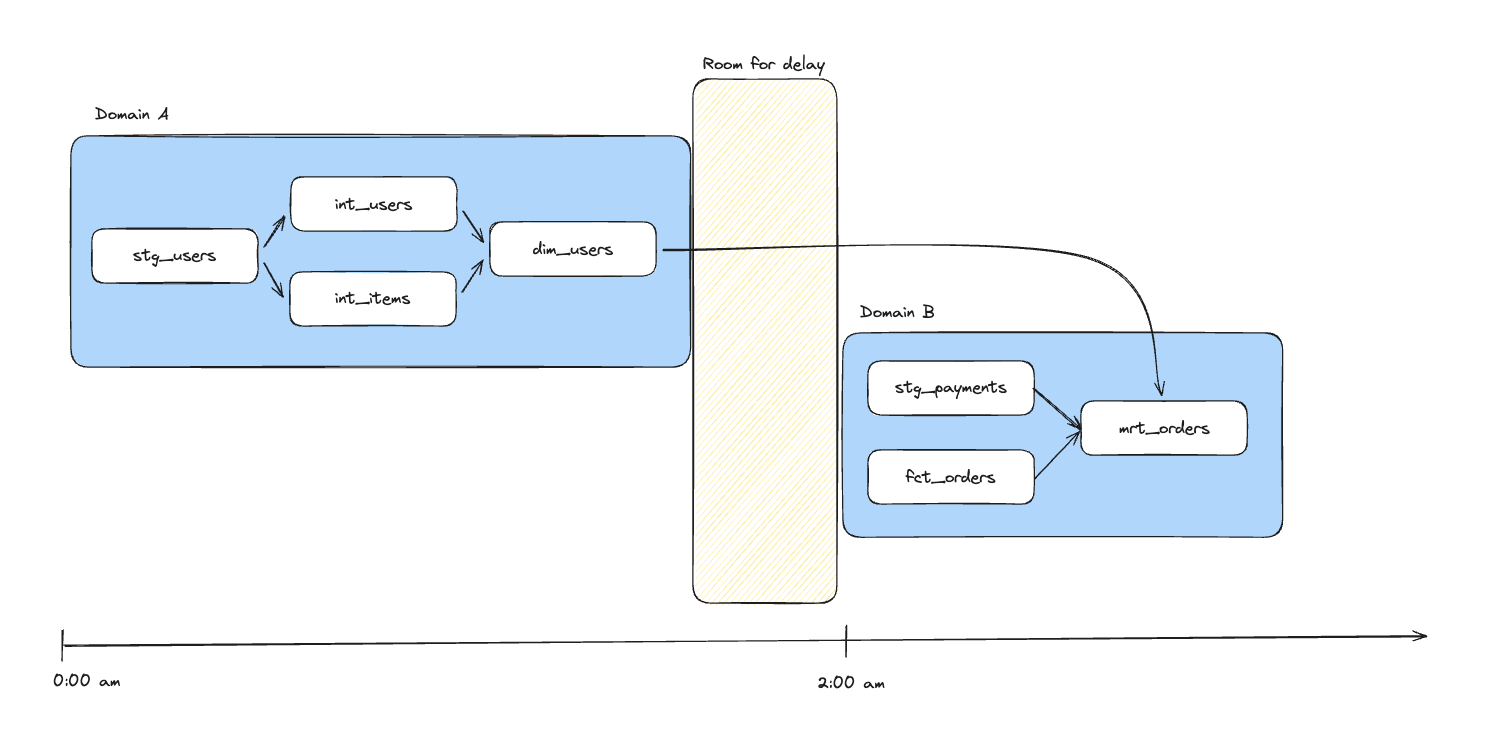

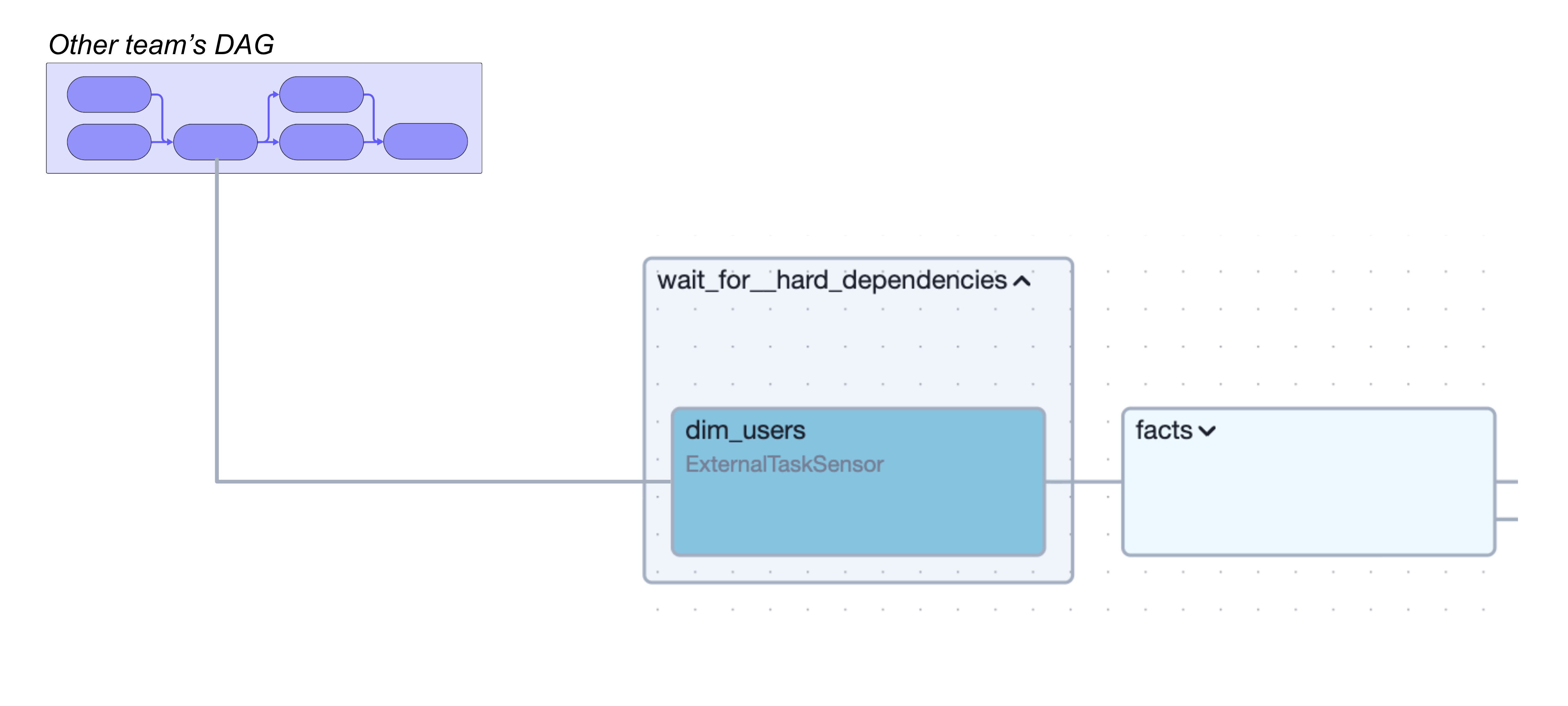

With task‑per‑model pipelines in place, the next step was to actually wire domains together. Practically, that meant setting up sensors that could wait on upstream work in other domains and only move forward when the right data was ready. Conceptually, the problem is simple (“don’t start this until that has finished”), but at platform scale the implementation details matter: who do you wait on, how do you express that, and how do you keep those relationships from turning into spaghetti?

Airflow already has an opinionated way to model cross-DAG dependencies: Airflow Assets. They’re event-driven, first-class citizens, and looked like the perfect fit for connecting domains without tight scheduling coordination.

Unfortunately, we found ourselves running into a hard limitation quite early on: Airflow Assets operate at the DAG level. An Airflow Asset update can trigger an entire downstream DAG, but we needed something more precise. Our pipelines are owned end-to-end by domains, and we wanted to keep that ownership boundary intact: upstream domains shouldn’t be “starting” other teams’ pipelines, and downstream domains shouldn’t have to understand (or care) how upstream work is split across DAGs or tasks. What we needed was task-level unblocking inside larger pipelines: resume this specific unit of work as soon as that specific upstream unit is ready.

We found a more fitting candidate in the ExternalTaskSensor. It lets a task in one pipeline wait for the completion of a specific task in another DAG, exactly the fine-grained dependency we were after. However, this came with two obvious downsides. First, if teams wired sensors by hand, we’d end up with a fragile web of hard-coded references that’s difficult to validate, painful to refactor, and easy to break silently. Second, the mechanism is polling-based and timeout-driven, and in real life upstream tasks sometimes finish after a downstream sensor has already timed out, turning “just rerun it” into an operational habit.

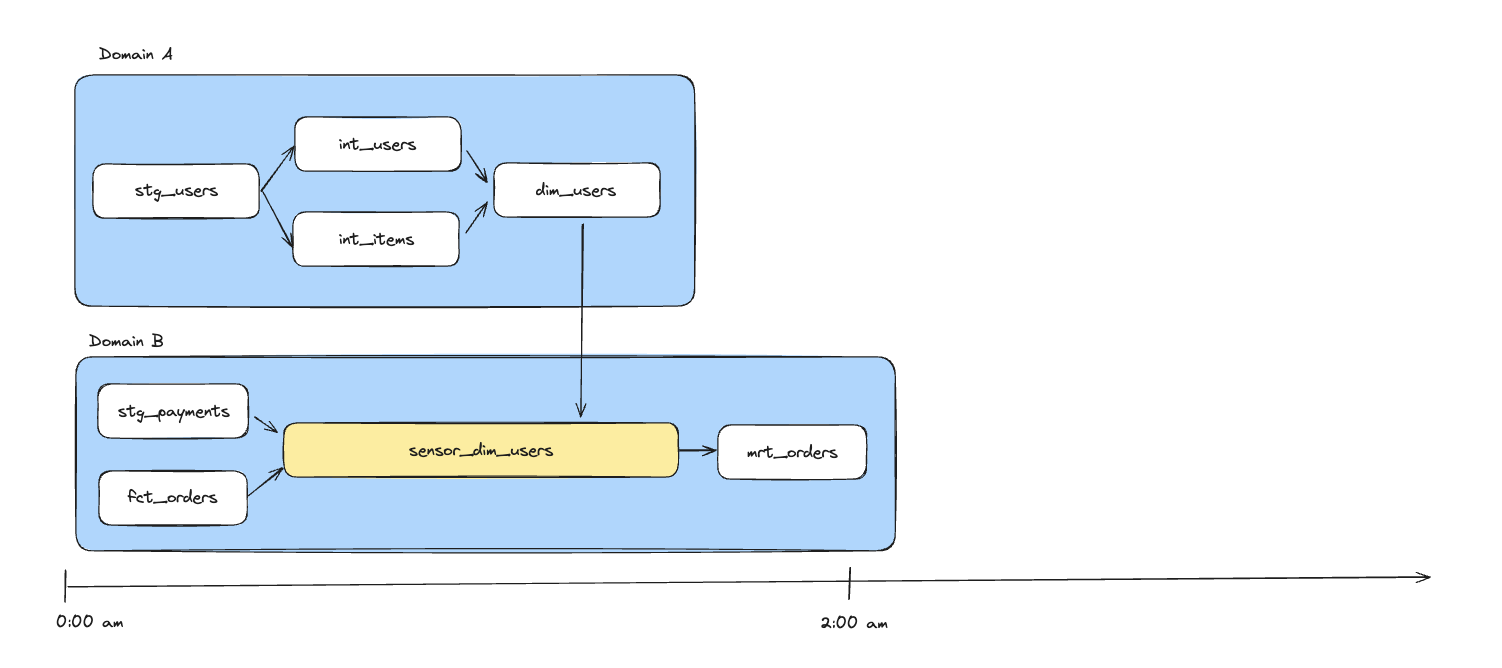

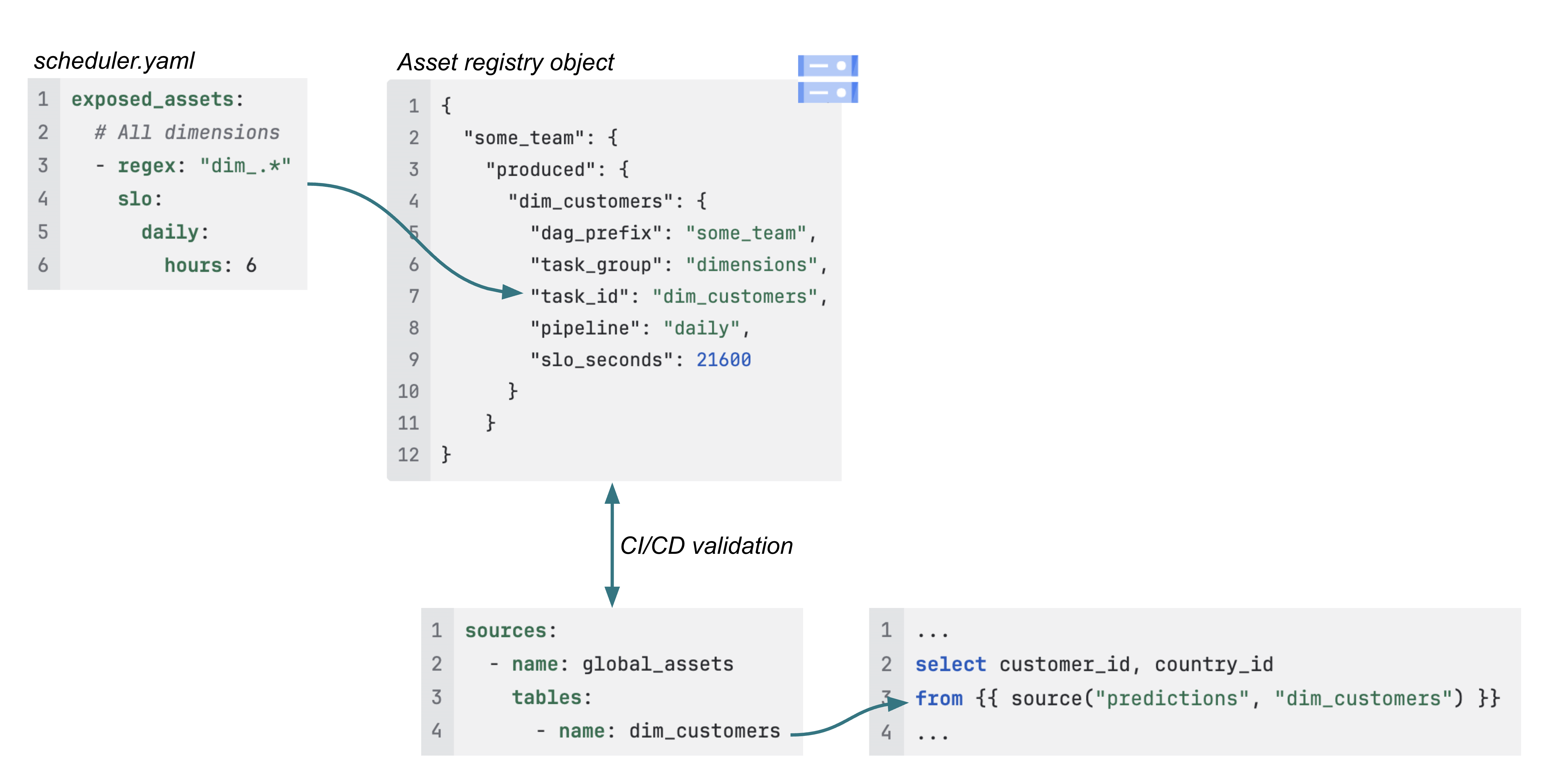

So we set out to enrich this candidate to ensure we solve both downsides. To achieve this, we built an Asset Registry: a central catalog of all tasks and their relationships. It knows which domain, pipeline, and dbt model each task belongs to, and how tasks depend on each other across domains. We use it in CI/CD to validate that upstream references are valid and to attach metadata like “when should my data be available?” and “which task should I poll for completion?”. This metadata is collected automatically, as it is already available in the dbt manifests.

For engineers, this means they don’t wire pipelines together directly. They simply say “this model depends on that model,” and the combination of DAG generator and Asset Registry turns that into concrete task‑level dependencies, distributed amongst decentralized data pipelines, using ExternalTaskSensor behind the scenes. This effectively solved the wiring problem. One down, one to go.

To solve the timeout problem, we use the registry too. When an upstream task completes, even if it’s late, we look up all downstream sensors that depend on it (including the ones that have already timed out) and mark them as satisfied via a completion callback. Downstream pipelines then continue automatically, without manual restarts.

From an engineer’s perspective, this complexity is invisible. They don’t restart stuck runs, chase timing mismatches between teams, or track who depends on what in their heads. The platform reconciles dependencies as tasks complete and makes the behavior transparent and deterministic: you can always ask the registry who depends on a task and why something did or didn’t run.

Turning Decentralized Data Modelling into a Breeze

Not only does our approach solve the dependency issues, it also sheds light on a complex and decentralized data landscape. In an intrinsic web of domain dependencies, it can become tricky to understand who depends on which data assets you own. This created a risky environment for our engineers to make changes to assets they own. Upon introducing breaking changes, like altering the schema, they were tasked with finding out which domains were using this asset. Often this resulted in many back-and-forths and meetings that could otherwise have been avoided.

Our Asset registry unlocks the ability in CI/CD to understand which model is going to be changed, and which teams depend on said model. We can simply collect these scenarios, and post them in the body of the PR the engineer is working on. By adding the Slack channel, we provide a simple and effective way to understand who to reach out to.

Why Everyone Needs a DAG Generator

A standardized DAG generator has become one of the most valuable pieces of our platform. Because every pipeline is created through this generator, we effectively hide DAG authoring from users and constrain them to a small, curated set of building blocks. Under the hood, those map to a limited number of Airflow operators and patterns we control, which means we only need to test and maintain a narrow surface area instead of a zoo of custom DAGs.

The trade-off is that Airflow has a huge ecosystem of operators and built-in features, and our generator only exposes a small subset of them. Sometimes that means we can’t use a capability straight out of the box, or we have to reimplement parts of it inside the generator to keep the interface consistent. Still, the leverage we get from standardization is worth it.

The interface for users stays stable: they describe models and dependencies in the same way, regardless of what’s happening underneath. This gives us freedom to change the generator’s output when we need to. If we want to tweak retries, swap an operator, or adopt a new Airflow feature, we update the generator and regenerate the DAGs. Teams don’t have to manually configure anything in their pipelines.

This approach really paid off when we upgraded to Airflow 3. We adapted the generated DAG structure and operators, rolled out the new generator, and were done. For engineers, the migration was almost invisible; for us, it was a controlled platform change instead of a manual cleanup of dozens of hand‑written DAGs.

And for most of our engineers, that’s exactly how it should be: they think in terms of data, while the platform quietly does its job in the background.

Appendix

We had the privilege to present this solution in more detail at the Airflow Summit in Seattle, PyData Amsterdam and Astronomer’s The Data Flowcast. Please find the links here if the above piqued your interests!